How to describe the feeling? I sit with a bowl of broccoli bacon chowder, ice water, air conditioning, and classical music playing in the background. The clean tile floors are cool to the touch, and I can feel my body temperature drop 10 degrees in the capitol of Dakar after leaving my village of Mbolo Aly Sidy

This morning I woke up under my mosquito net, the pathetic three-legged donkey awkwardly standing in my way as a walked to my room, carrying my blanket and pillow back inside, keeping an eye out for frogs. The mosque hadn’t even began to chant because I was up before the world to leave Mbolo Aly Sidy for the last time. All was still in the world except for my heart, which was breaking with every beat; the beats becoming rapid with tension and nervousness and unhappiness and loss… even before I had left the compound. I made sure my baggage was together and rechecked my empty room one last time and returned to my bed to wake up my mom, who had been awake, probably since I had gotten up. She told me to lay back down until the driver called. I laid there next to her looking up at the circle made by the net and how it enclosed us both like a hug, protecting us, keeping us together, and I turned away from her, crying as silently as possible.. Then the phone rang: the driver was coming. Coming to take me away from this life, to another complete opposite so drastic it hurt to think about. Here I am in a life, so comfortable, so accustomed, so inclusive and loving… and here I go. I wake up Malick, my brother, to help carry my bags and we haul one at a time out to the road. I sit on one bag, my mother on another, and my sister Kadja on the third. In the dark, I begin to cry, trying so hard to stifle my sobs. My mother’s breathing quickens and I know she is crying as well. No one speaks. My tokara (namesake) arrives in silence, gogol Hawa arrives in solidarity, Mista (my new friend from Sierra Leone) arrives to travel with me to Dakar. We all sit in silence, muffled sobs breaking the darkness. A luminescence in the distance signals the car’s arrival.

Gardo ko kootoowo – the one who comes, must always leave

Bags packed on top, we say our goodbye’s. Left hands given, as a way of saying ‘because I have offended you with my left hand, we must meet again so I can make amends to you.’ I can’t speak. No one speaks because all are crying. I can’t look anyone in the eye because it’s just too painful. My sister Kadja, I hug her, her body feeling so small and shaking with sobs. My mom puts her hand on my shoulder; it’s time to go. Mista helps me into the car and holds me while I cry, off and on, all the way to Ourossogui. The sun beginning to rise, I curl up to catch some sleep.

These last few days in village have been undoubtedly the best. After spending the night in the ‘wallo’ fields and then on to have my extreme going-away party, I haven’t slept much and haven’t wanted to. I came to this village as Dana: not knowing what I wanted to do in life, where I wanted to go, unaware of this unknown culture and language, unsure of myself and my surroundings, timid. I left this village as Coumba Demba; a name that has become my personality, my persona, my strength. Coumba Demba is strong, self-aware, aware of others and how much each and every person must be valued, conscious of family ties, and loving of all. Dana loved all as well, but Coumba Demba has found a new depth to this emotion. My mother Kadja reminds me, by grasping her breast, ‘an ka bii am, mi moynii maa,’ You are my child, I raised (literally, breastfed) you. And it’s true. This community raised me from being Dana into being strong, confident Coumba Demba Thiam. They helped me along every step of the way, telling me what to do and what not to do, how to eat, how to dress, etc. Now I am at the point where I can call them out for doing things wrong and we all laugh about it.

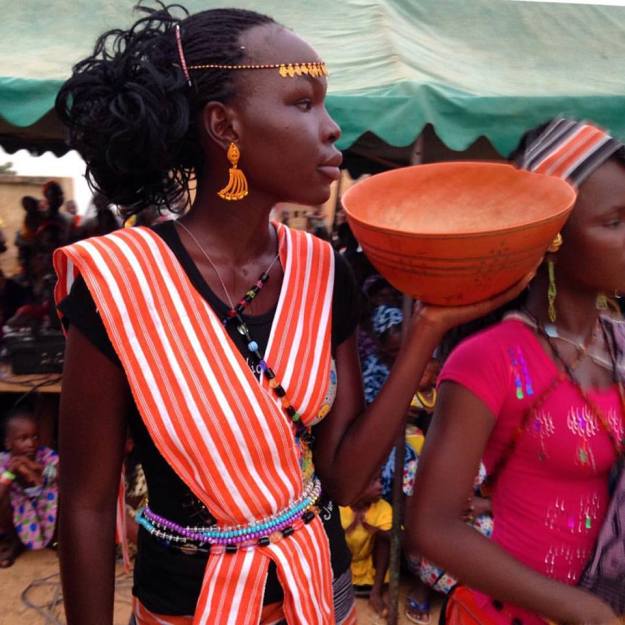

So now working backwards a little, let me tell about my going away party. The idea started off as a small family gathering in my house. Then Maxi Krezy, world-renowned, and one of the original Senegalese rappers, said he was planning on coming home from America in time to see me before I left. This changed things. Also, thinking of all the people I wanted to see at the party, I realized I was going to be inviting more than would fit in my compound. The party then moved to the school. I wanted the reason for this party to be to celebrate the Pulaar culture and the culture of the Fouta. This is the culture and the people I have grown to love so much. I have written a previous post about the loss of culture in this area and the shift towards Western ideals, which has its positives and negatives, so this day was to celebrate the roots of the beautiful culture and the people who I had learned from and appreciate in so many ways.

This meant, however, a lot of organization, which I did not anticipate. I had to organize the participants of Thiossane (cultural wear), the dance group, and the theater group. I decided on ‘education’ as the theme of the day, since ‘agriculture’ is not really something I need to advocate for and the education of women in this area is a difficult subject that I feel passionate about. Our theater production focused on the importance of staying in school and Maxi Krezy had already expressed interest in helping me discuss the importance of education and women staying in school during the panel discussion.

I couldn’t stop smiling the entire day out of sheer joy. From the second I woke up, I was running. We made a huge feast of rice and meat for lunch, complete with fancy drinks throughout the day, afternoon snacks of begniets and popcorn, and just all-out happiness.

Alicia, my site-mate/twin/support network/sister, helping to serve my lunch

My friends came from all over the Fouta! Maxi Krezy came from Dakar (he made the longest trip), my friend Amadou Diallo, from Ndioum, came back from Dakar right in time for the event, Baba Sy came from Aire Lao, guests also came from Diaba, Bogguel, Loumbal, and even people from St Louis showed up for the show! My neighboring village, where I spent most of my working time, said that night, Mbolo Birane was empty. No one was there because everyone had come to my party and stayed the night in my village. All of the people I wanted to see before I left, showed up. All of them! Even thought I didn’t get to have much time to talk to them because of the huge-ness of the event, just seeing their faces or hearing their speeches made my heart full of happiness.

My mom broke through the crowd to come dance with me!

Ndiyam, so boyyi in channgol fof, ko mayo fatii – the water that stayes for a while in the channel, must eventually go to the river (all good things must come to and end)